Peking University, February 18, 2022: Nobody knows precisely who gave the Wild Grass Bookstore its name, but everyone who ever had the chance to visit its cramped quarters on the campus of Peking University agreed, they got it right.

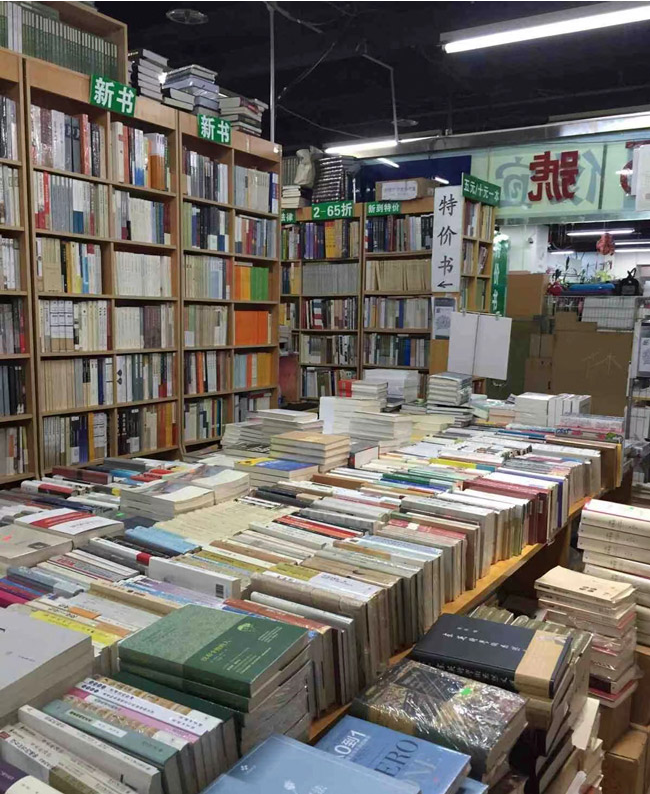

An independent bookshop stuffed into the corner of an underground campus supermarket, books seemed to sprout there like weeds: on shelves, on the ground, atop stacks of yet more books. This wasn’t some bourgeois haven better suited to Instagram than browsing; there was no coffee or trendy French playlist, only stale air and the smell of manager Zhao Liang’s cheap cigarettes.

Although known to students as “Boss Zhao,” the title is actually a misnomer. The bookstore is owned by Zhao’s brother-in-law. After dropping out of high school around the turn of the millennium, Zhao followed the well-worn migrant track to the city, working for a time in a toy factory in the southern province of Guangdong before joining his brother-in-law’s Beijing bookselling business in 2002. Five years later, he was appointed manager when Wild Grass relocated to the Peking University campus.

Zhao could be mistaken for any number of similar small businessmen in Beijing, at least until he opens his mouth to guide curious students through the store’s selections of Rousseau, Wittgenstein, or obscure Chinese classics. He never talks about his own reading preferences, but he’s known on campus for an almost magical sense of foresight, always seeming to get books in stock just when students need them. Some even joke that he has a better sense of how Peking University students’ research is going than their professors.

Books on display at the now closed Peking University campus location of Wild Grass Bookstore in Beijing, 2015. From @芳美明子 on Weibo

The magic here isn’t the result of recommendation algorithms like those that have powered Amazon and JD.com to dominant market positions. Rather, it’s the result of Zhao’s tireless efforts to keep up with the latest intellectual trends on campus. In the early days, his main source was gossip overheard from shoppers. Then came WeChat, the country’s ubiquitous social networking app.

Each WeChat account is capped at a maximum of 5,000 contacts. According to a 2016 report by the Peking University campus newspaper, in the span of two years, Zhao had filled up two accounts and was working on a third. To his vast network, including students, teachers, and one-off visitors, he appeared as “A Zhaoliang” — a clever trick to make sure he stayed at the top of everyone’s contact list.

When Peking University philosophy professor Li Meng published his first major book in 2016, students couldn’t find it anywhere. After all, Amazon and other online bookstores were hardly lining up to stock the latest works of the history of political philosophy. But shortly after I posted on WeChat asking if anyone knew where I could get a copy, I got a reply from Boss Zhao: “Arriving soon. Come (to the bookstore) tomorrow.” Later, whenever he recalled this episode, he couldn’t help but smirk when talking about his “Brother Meng,” referring to the professor by his first name as if they were old pals.

Keeping an independent bookstore afloat in the e-commerce era is no easy feat. Last year, the New Yorker published a story on a Kansas bookseller’s lonely fight against Amazon. Danny Caine, the owner of the Raven bookstore, announced on Twitter that he would no longer compete with Amazon on price. Customers, Caine suggested, should be willing to pay higher prices to preserve their local culture.

Chinese booksellers face similar challenges, as major online sales platforms offer increasingly economical and convenient ways to buy books. To survive, many Chinese independent bookstores have transformed themselves into trendy hang-out spots and expanded their offerings to include cutesy stationery and hip clothes. Books have been pushed into the background, functioning like the inoffensive tunes piped in over the speakers.

But Wild Grass stuck to the traditional playbook, offering discounts competitive with the e-commerce giants. There was even a large banner on the bookstore’s front door: “Price has the final say.”

An exterior view of the now closed Peking University campus location of the Wild Grass Bookstore in Beijing, 2015. A sign reading “price has the final say” can be seen on its front door. From @芳美明子 on Weibo

There were good reasons for the strategy: Wild Grass’s core customers were usually broke students, and the store’s limited space made running a café or salon on the premises difficult. And for years, it worked: Zhao’s low prices kept the bookstore’s unique flavor and earned his customers’ loyalty. This artless bookstore formed a perfect symbiosis with the university, as students and professors eagerly snapped up titles that no one elsewhere would cast a glance at.

Yet the bookstore wasn’t immune to broader changes in the country’s business environment. In 2017, Peking University announced it would “optimize” all the existing commercial entities operating on campus. In earlier years, bookstores, convenience stores, and snack bars sprouted up on school grounds like, well, wild grass. Many of them were operating without a formal contract or without having gone through an open bidding process. So the university declared it would hold a public tender process to make sure every storefront contract on campus was awarded through fair competition.

It didn’t take long to see the writing on the wall. Reading through the bidding proposals, the discrepancy between the thick, glossy submissions of the chain bookstores, with their promises of low prices and student-friendly environments, and that of Wild Grass, which was as primitive as the store’s name, was obvious. How could a bookshop run by a high school dropout win over judges who were vowing to emphasize professionalism and transparency over personal relationships?

It couldn’t. When the bidding results were released, Wild Grass found itself shut out.

Forced off campus, Wild Grass relocated to another corner of yet another underground supermarket, this one on a main road near the university. Some longtime readers still visit from time to time, but it’s no longer a place where students and visiting scholars can grab a book a stone’s throw from their dorms. Many freshmen have never even heard of it. The chain bookstore that took its place, meanwhile, has struggled to win over Zhao’s former regulars.

Separated from the soil that had nurtured it, Wild Grass had lost its vigor even before the pandemic came. Then, in January, word came that Wild Grass’s landlord was planning to terminate their contract with the bookstore. Barring an unforseen turn of events, February is likely Zhao’s last month in business, at least at a physical location. Although he may continue selling books through WeChat, the Wild Grass Bookstore, a time capsule back to a simpler era, now seems lost forever.

Looking back on the past 20 years of Wild Grass, I can’t help but think about the words by Lu Xun, modern China’s most celebrated writer, in his 1927 essay collection of the same name: “From the clay of life abandoned on the ground grow no lofty trees, only wild grass.” Someday, hopefully, we’ll realize that a little wild grass on an otherwise perfectly manicured landscape isn’t a bad thing.