Bo Shining, a 49-year-old chief physician from the Intensive Care Unit of Peking University Third Hospital. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Doctor offers readers a better understanding of medicine at its most critical point, Yang Yang reports.

Bo Shining, a 49-year-old chief physician from the Intensive Care Unit of Peking University Third Hospital, arrived at the interview on a hot summer afternoon after a night shift. With an iced Americano in hand, he answered the questions with a doctor's sobriety and reason.

But when he recalled the medical case that inspired him to become a doctor specializing in intensive care, a teardrop slid down from the corner of his right eye.

More than two decades ago, Bo chose clinical medicine as his university major because "it's difficult to get into", he says.

In his fifth year of university in 1997, Bo, a curious intern at a hospital, came across a very important patient — his 20-year-old younger brother, also a university student, who was critically ill as his kidneys were failing quickly due to unidentified reasons.

Without a pathological examination basis, and judging from the symptoms, Bo believed that the cause was rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, a dangerous disease in the kidneys with a mortality rate of 80 to 90 percent within six months without proper treatment. Even if some patients survived, they would have to rely on renal dialysis for the rest of their lives.

Considering such a terrible prognosis would happen to such a young man who was otherwise very healthy, and seeing his father, a tough man who served in the army, crying, tears rushed from Bo's eyes.

Desperate to save his younger brother, Bo misjudged the cause of the disease. Luckily, a reputed doctor corrected his mistake, saying that it might be epidemic hemorrhagic fever but they needed a test to confirm the diagnosis.

Bo took his brother's blood sample to a provincial center for disease control that was 3 kilometers away by bicycle. On the second day, it was raining heavily. When Bo took the test result that confirmed the expert's diagnosis, he rushed back in the pouring rain, forgetting his bike.

Soon his brother fully recovered from the disease without any long-term effects.

"This is the first critical case that I encountered in my career. I realized that illnesses can quickly devastate a family and intensive care medicine can save many people's lives," he says, which is how he decided to become an ICU doctor.

In 2001, after graduating from the Peking University Health Science Center, Bo entered the ICU at PKU Third Hospital.

As he has strived to keep critically ill people alive and experienced life and death every day for more than two decades, he began questioning how to improve people's ability to cope with diseases.

"After all, the number of people that doctors can save is limited. If you wait until an illness becomes severe before going to the hospital, even the most skilled doctors will find it difficult. But if people can gain a comprehensive understanding of medicine and grasp basic medical knowledge, perhaps by attending a 'concise medical college' through reading, then we won't be so helpless when faced with diseases," writes Bo in the preface of the book Bo Shining Yixue Tongshi Jiangyi (Medicine in a Nutshell), published in 2019.

The book was one of the first of its kind in China, in which Bo summarized his understanding of health, disease, life and the medical profession based on his 18-year work experience.

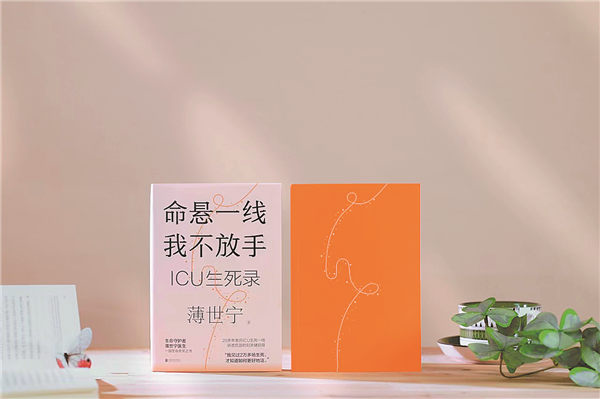

His award-winning book about life and death at the ICU. [Photo provided to China Daily]

By reading the book, people can have a quick understanding of the essence of medicine as well as doctors' diagnostic and treatment methods. About 310,000 copies of the book have been sold so far.

Last year, his second book, Mingxuan Yixian Wo Bufangshou (Never Let Go, Life and Death at the ICU) was released. So far, more than 100,000 copies have been sold and in April, it won the Wenjin Book Award, China's top book award.

Unlike the first book, the latest one focuses on another side of medicine — humanity, because "medicine is not only a science but a study of humanity", he says.

"That is, how to comfort your patients. Often, comforting and caring for your patients can have the same effect as medication," he says.

Based on his 22 years of experience during which he was involved in about 10,000 intensive care cases, Bo chose 19 for this book.

The 19 real ICU stories include a terminally ill wife who was abandoned by her parents, husband and mother-in-law, and an elderly woman who wanted to go back home at the end of her life.

"The books explore many topics such as saving money or saving a life, how to build trust between doctors and patients and how to say goodbye to loved ones. To better understand the patient's feelings and choices, Bo flew to many locations to interview them," says Wei Ling, editor-in-chief of Xiron, a Beijing-based publishing company that published Bo's book.

Each story showcases a theme that Bo says he wants to explore — how to inspire and protect patients' "will to live" at critical junctures, what is rational love, what is "a good death "for terminal patients, and more.

The book also talks about sympathetic doctors whose strong desire to save people may cause misjudgment and their continuous improvement in medical skills, risky choices and strong minds.

On Douban, a major Chinese review platform, nearly 1,200 readers rated the book 8.9 points out of 10. Many readers are deeply touched.

"This book gives readers a good lecture about life and death, allowing people to know that treating diseases and saving lives are not only scientific issues but also an issue of humanistic care, which is what common readers need to learn about," Wei says.

Reading the 19 cases is like watching the US TV drama Doctor House, in which the prestigious Doctor House detects the cause of a series of unidentified illnesses, saving lives and exposing human nature.

In the book, a case that has touched many people is that of a "stubborn" old man who refused to give up on his wife, whose brain was dead due to an oxygen shortage caused by heart attack.

Every time Bo came to the ward, the husband followed the doctor around, suggesting possible treatments he read about or questioning the doctor about why he had not tried this method or that. Young Bo understood that the old man blamed himself for not saving his wife in time, but sometimes he lost his patience.

"In 2005, it was easy for me, a young doctor who mastered some knowledge, to be arrogant and cold," he says.

Half a year after the heart attack, on his wife's birthday, the old man dressed up and sang a song to his wife in front of all the doctors and nurses, who seemed to hear the song as two teardrops slid down from the corner of one of her eyes and then she immediately died.

"I was touched that day when the old man sang a song for his wife, but at that time I had not fully understood the whole thing," he says.

Bo wrote a long essay about this case. When he showed the essay to the couple's son, who lived abroad and arrived several days after his mother died, the son knelt in the corridor and burst into tears.

Many people are touched by the deep love between the couple, but Bo says the case gave him some other inspiration.

"Everyone aims for healing but they forget that we all have to experience one incurable case, that is, death. When that happens, how should we treat the patients?" Bo says, adding that "this case answers that question".

"The case reveals the essence of medicine," he says.

"Healing is a comfort. When patients suffer too much, relieving his or her pains is also a comfort. The treatment process is a comfort. However, every person will experience an incurable case. To not let go when it's incurable is perhaps the ultimate comfort humans can offer to one another. This kind of comfort allows the dying to do so peacefully and the living to live without regret," he writes.

That is, Bo says, the essence of medicine, which determines how one understands the definition of a good doctor.

To be a good doctor, "you need to be knowledgeable and intelligent, you need a strong mind to face complicated and urgent situations, and after you become more and more skillful and tough, you still need to be able to hear the weak cries of the common people, their hidden pains," he says.

Source:

China Daily

Written by:

Yang Yang