Why new energy 'overcapacity' claims are false

Aug. 13, 2024

CAI MENG/CHINA DAILY

Some Western nations have been touting the so-called "overcapacity "problem of China in recent years, alleging that China's "excess capacity" in the new energy sector has disrupted and threatened the international market. Consequently, protectionist measures have been adopted against some Chinese products, such as electric vehicles.

The term overcapacity refers to a scenario in which production capacity of an industry exceeds market demand and expected levels, indicating a disequilibrium in the market's supply-demand relationship. However, it should be noted that demand is a highly volatile factor that is very susceptible to influence by macroeconomic fluctuations stemming from changes in investment and consumer behavior.

There have been numerous misconceptions surrounding the concept of overcapacity. In fact, overcapacity is often not the result of excessive supply but rather cyclically weak and insufficient demand. Consequently, insufficient demand usually necessitates macroeconomic adjustments — not just supply-side adjustments to reduce production capacity, but also demand-side policies aimed at expanding the market and aggregate demand.

For instance, market entities often anticipate demand for certain industries and products based on fundamental factors such as medium- to long-term income levels and consumer preferences. When these expectations of future market demand are considered, it becomes clear that industries in China like wind power, photovoltaics, EVs and infrastructure construction cannot be deemed as having overcapacity. The ample supply in these industries is merely a matter of potential demand not being fully realized. Given rising trends in consumer demand, stable capacity can quickly turn into supply shortages in a few years.

True overcapacity involves a long-term, structural surplus in certain products, where demand shrinks as income grows and living conditions improve. Some industries experience an absolute decrease in demand, such as outdated products or those without much market demand. In those cases, market competition will play a role in driving out inefficient suppliers and curbing overcapacity.

To determine whether a market truly has overcapacity, both short- and long-term demand must be considered. The income elasticity of demand metric — which measures the responsiveness of consumer demand for a product to changes in income — is suitable for this assessment.

For products with a YED greater than 1, demand increases by more than 10 percent for a hypothetical 10 percent increase in income, indicating that production capacity should be expanded.

Conversely, for products with a YED between 0 and 1, demand increases by less than 10 percent for the same income increase, suggesting a need to curtail capacity expansion if a supply-demand equilibrium is to be reached.

For products with a YED equal to or less than 0, demand remains stable or decreases as income grows, requiring not only a halt in capacity expansion, but also a reduction of existing stock.

For example, in the 1990s, China experienced significant overproduction in the textile sector, with the YED for clothing products being less than 1, indicating that growth in demand for clothing lagged behind growth in income, leading to heightened market competition.

Similarly, over a decade ago, China faced overcapacity in the steel industry. The market was saturated with low-quality steel, resulting in a scenario of "low-quality steel products driving out high-quality ones", ultimately pushing some high-quality steel producers out of the market.

As the overproduction of low-quality steel was not only a short-term issue but also projected to persist over the next 10 to 20 years, structural adjustments within the industry were needed, necessitating regulatory intervention and policy guidance.

The occurrence of seeming supply-demand imbalances as a result of forward-looking inputs to promote the development of promising new technologies and industries should not be deemed as "overcapacity". In the long term, market demand for products from those industries would increase. Potential market demand for many such products does exist, but it has not fully materialized due to immature support infrastructure.

Moreover, there is often a lag in market and consumer awareness, and acceptance of new technologies and products takes time.

For example, the rapid development of big data, cloud computing and artificial intelligence has led to the construction of intelligent computing centers and supercomputing centers. However, some large language model applications are not yet fully developed, and the supporting computing networks remain inadequate. This does not mean that the construction of computing centers constitutes overcapacity. As relevant downstream sectors develop collaboratively, expanded capacity is expected to be effectively utilized.

In terms of new technologies and industries, therefore, appropriately forward-looking inputs are necessary, and the resulting supply-demand imbalances are common and should not cause undue concern.

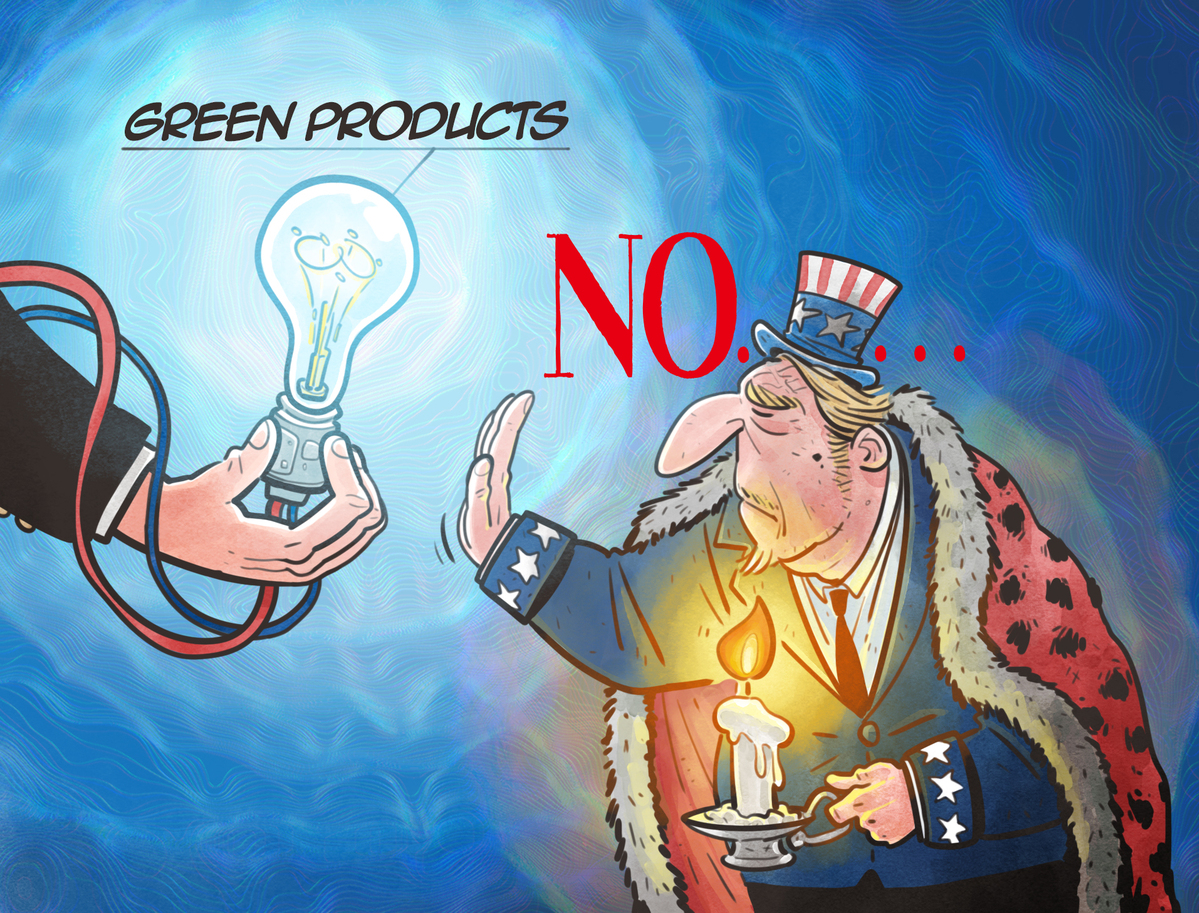

In fact, claims by some Western countries that certain Chinese industries have "overcapacity" actually have more to do with politics than the actual supply-demand balance scenario in those industries. They have touted such claims mostly to protect their relevant domestic industries.

From an industrial perspective, those Western countries typically resort to two strategies to maintain their global dominance in some sectors — aggressively advancing their own development or hindering the progress of others. Despite the repeated use of technological blockades and economic sanctions, such measures have not been effective in curbing the export of Chinese renewable energy products.

China accounted for over half of the world's new photovoltaic installations last year and approximately 70 percent of the global market share for key components such as photovoltaic modules and wind turbines. Additionally, Chinese EVs represented more than two-thirds of global EV sales. Given the evident popularity and competitiveness of these Chinese products, trade-prohibitive measures based on "overcapacity" allegations not only disrupt international trade, but also harm consumers in countries implementing blockade measures by depriving them of access to high-quality, reasonably priced products and services.

Overall, the United States and Europe still have stronger research and technical capabilities than China in many areas. Even in the new energy sector, China's technological advantages are not overwhelming. The US and Europe still lead in some cutting-edge high-tech fields. China's success in the industrialization of new energy technologies is closely linked to its demand-side support for players in those industries. By creating and encouraging demand for new energy products, China has successfully incentivized the rapid industrial application and upgrading of new energy technologies.

For example, in the early stages of EVs, China's industrial policy focused on creating and stimulating market demand, which has proved successful. Driven by market demand, Chinese EV companies have developed at a fast pace through continuous technological innovation, complete industry and supply chains, and vibrant market competition. Such success could not have been achieved by simply subsidizing the producers of EVs.

The writer is a professor of economics at the Guanghua School of Management, Peking University.

Source:

China Daily

Written by:

Chen Yuyu