Peking University, June 17, 2025: Natasha, whose Chinese name is Li Xiang (李想), was a Swiss exchange student at Peking University in 2024. Born in Switzerland to a Swiss father and a Chinese mother — the granddaughter of Franklin C.H. Lee (Li Jinghan 李景汉) — Natasha came to China seeking to uncover the family legacy and academic contributions of her great-grandfather.

Natasha in the Department of Sociology of Peking University

In March 2024, Natasha visited the Department of Sociology at Peking University, where she was received by Professor Tian Geng. He introduced her to the academic work of Franklin Lee and helped her get in touch with other universities where Lee had worked, allowing her to gain a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of her great-grandfather’s life.

Professor Tian Geng talking with Natasha

Franklin Lee is recognized as one of the founding figures of Chinese sociology. During his academic career, particularly at Yenching University (now closed), he conducted groundbreaking fieldwork in Ding County, Hebei Province, and in the outskirts of Beijing. His influential works — including

The Ding County Survey,

Rural Families in the Suburbs of Beijing, and

Methods of Field Social Survey — laid the foundation for the development of sociology as an academic discipline in China.

Natasha first heard about her great-grandfather when she was 12. At the time, she only knew fragments of his story. But about six years later, her curiosity deepened, prompting her to conduct extensive research. She was amazed to discover the pioneering role he played in Chinese academia. “I must go to China to learn more about my great-grandfather,” she told herself.

Natasha (6th from the right) in a group photo with other students and Professor He Shu (5th from the right) from PKU School of Journalism & Communication

Lee’s academic journey can be divided into several major stages. After graduating from University of California in the United States, he returned to China and began teaching at Yenching University. There, he focused on training students in sociological research methods and often led them on fieldwork trips to rural villages. His early research emphasized rural families, and he conducted systematic surveys in the suburbs of Beijing.

Lee (2nd from the left) did research in Ding County

Later, Lee left his faculty position to fully dedicate himself to the Ding County Survey Program, one of China’s earliest large-scale, data-driven social research projects. In Ding County, he faced two major challenges — communicating academic concepts in a way that rural peasants could understand, and designing a rigorous system for data collection and analysis. Over eight years, he led a comprehensive quantitative study that culminated in his landmark book,

The Ding County Survey.

However, his research was disrupted by the outbreak of World War II. When Japanese forces invaded Beijing, Lee and many other scholars were forced to flee. He relocated to Yunnan, in southwest China, where the National Southwestern Associated University was established. There, he resumed teaching and research under wartime conditions.

During his journey to Chongqing, China’s wartime capital, Lee continued to write. He produced numerous essays and memos, passionately arguing that social science had a vital role to play in national development. He believed that only through a deep understanding of its people and culture could China chart its path forward.

After the war, and following a series of institutional transitions, Lee returned to academia at Renmin University. Drawing from his background in demography, he expanded his work into quantitative economics and labor studies. His career entered its final academic phase in the late 1970s, when he re-engaged with the field of sociology, bringing his decades of experience full circle.

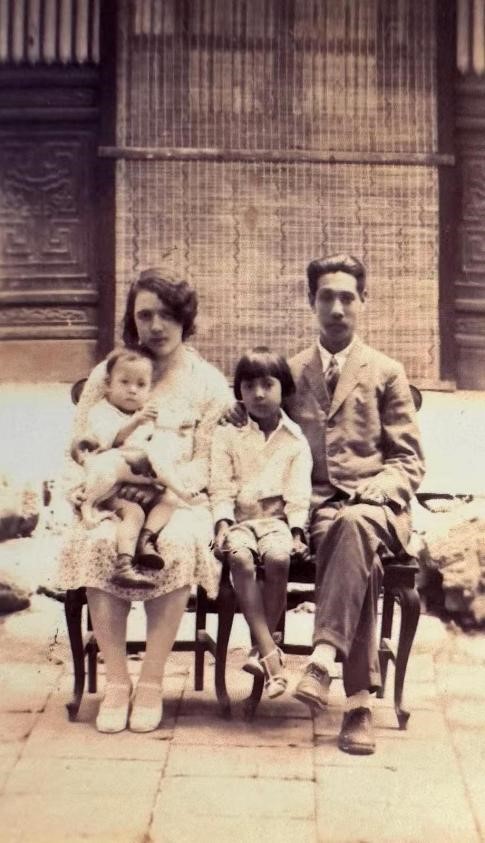

Natasha’s grandfather (the little boy on the woman’s lap) and her great grandparents

In 1962, his granddaughter — Natasha’s mother — was born. For Natasha, Franklin Lee was first a family figure before he became a historical one. In her imagination, he is a kind and gentle elder, then a serious and meticulous scholar. “Every time I see his smile in old photos, it feels like he never really left,” she said. “If I had the chance, I’d love to sit with him, talk about his life, and hear how he saw the world.”

Although Natasha never met her great-grandfather in person, she feels a deep connection whenever she sees or hears his name. She understands why he chose to focus on rural areas rather than urban centers — he himself came from a farming family. His mission was to uncover the realities of Chinese farmers, who made up the majority of the population but whose voices were often unheard.

This connection continues to shape Natasha’s academic path. Now majoring in communication and media, she hopes to integrate her field with rural sociology, continuing her great-grandfather’s legacy in a modern context. With the support of the Department of Sociology at Peking University, Natasha recently had the opportunity to visit Dingzhou City (former Ding County) — the very place where Lee conducted his foundational research nearly a century ago.

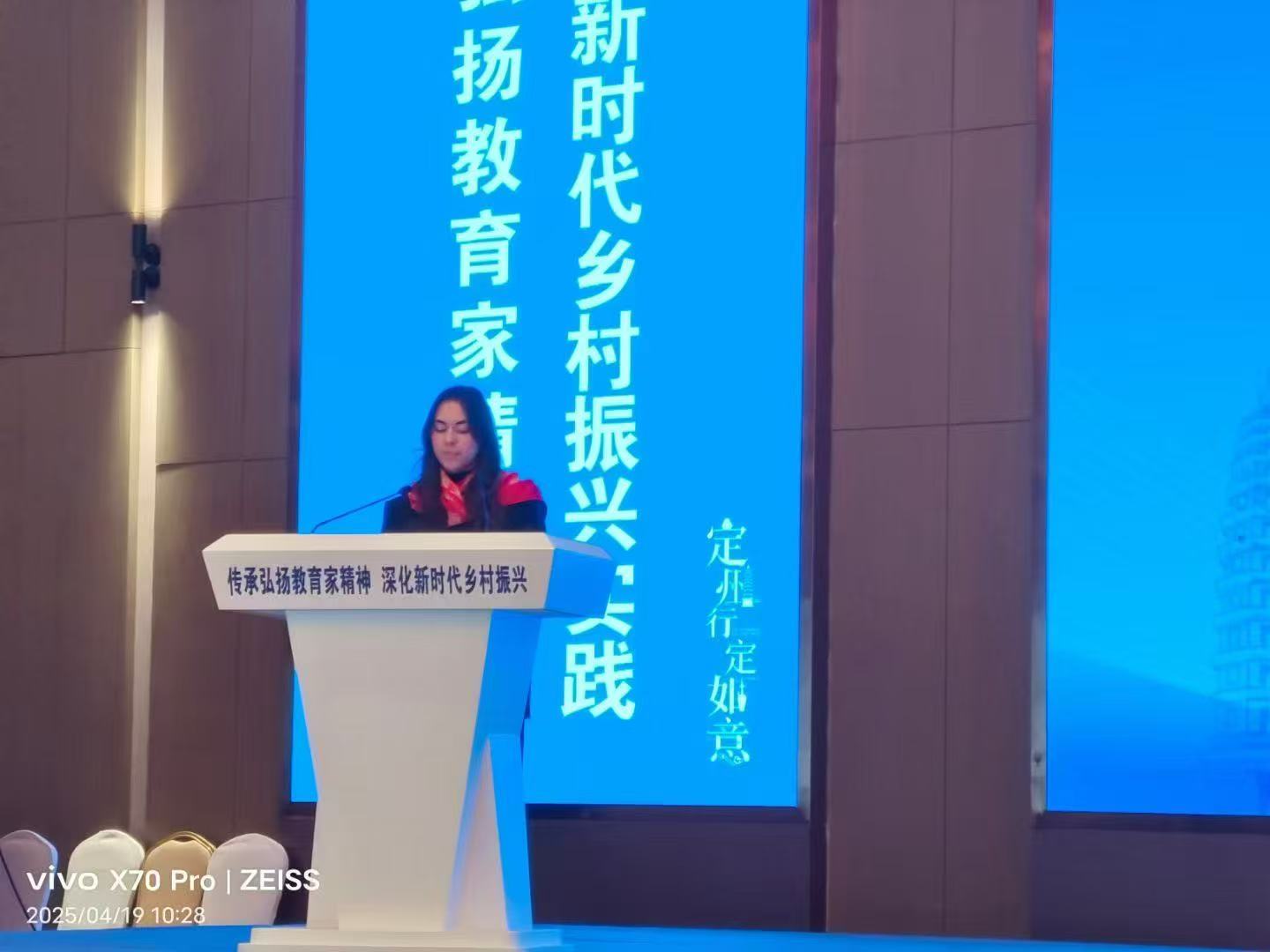

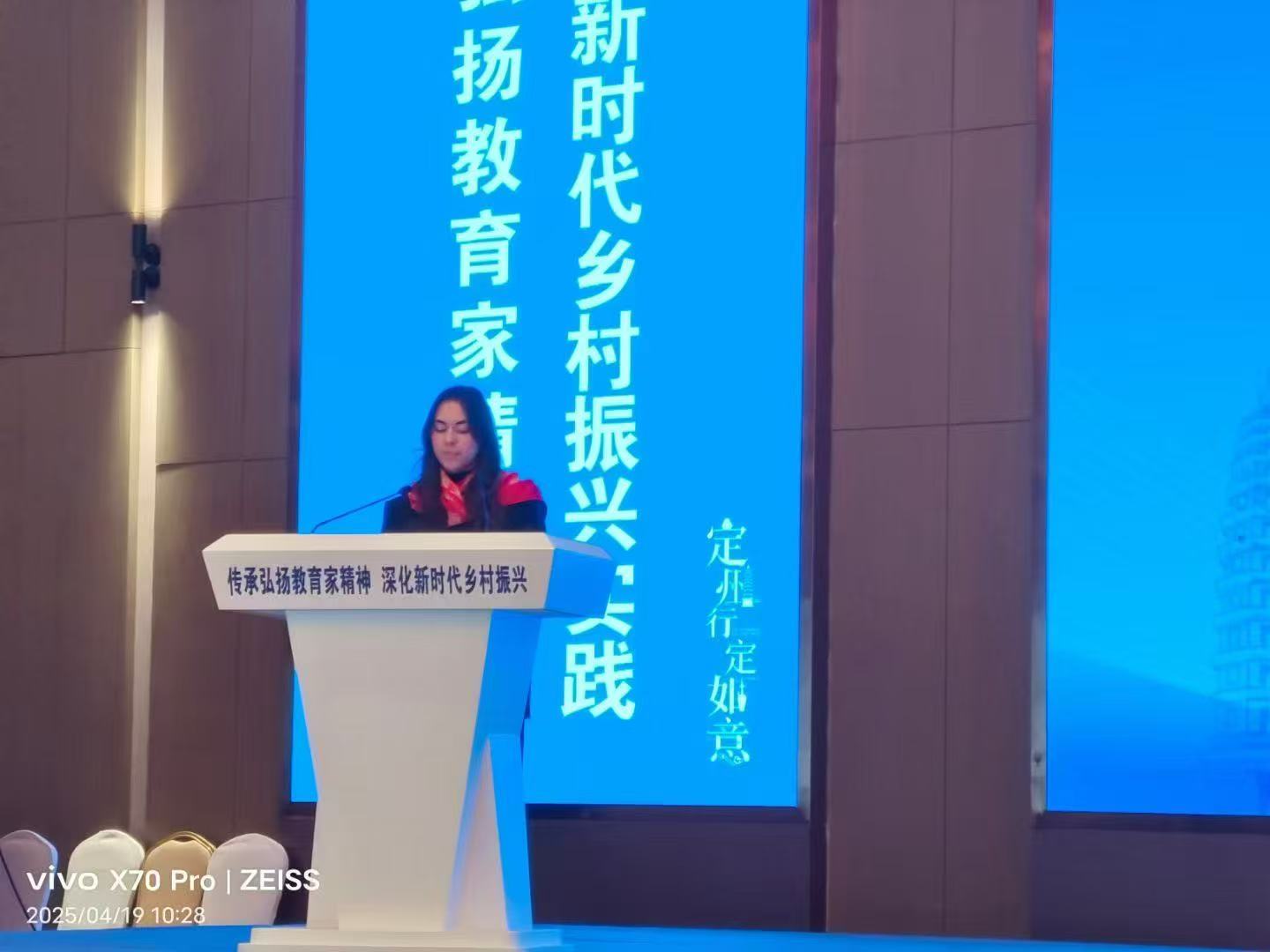

Natasha gives a speech during a sociology conference at Dingzhou City

She attended an annual sociology conference held in Dingzhou City, which commemorated the groundbreaking Ding County Experiment and honored the scholars who contributed to it. The event brought together not only academics and researchers, but also descendants of the original contributors, including families of Franklin Lee and James Yan (Yan Yangchu). Natasha was invited to deliver a speech at the conference.

In her speech, Natasha shared reflections on both the human and academic dimensions of her great-grandfather’s work. She emphasized that Franklin Lee approached research not only with intellectual rigor, but with humility and compassion. “He understood that meaningful research required more than methods and data,” she said. “It required connection — empathy, listening, and openness.”

One anecdote that inspired her remarks was the story of a simple cup of water offered to Lee by a farmer during his fieldwork. That small moment, she explained, symbolized the mutual respect and human bond that underpinned her great-grandfather’s work. “It wasn’t just about pioneering Chinese sociology or adapting theory to local contexts,” Natasha noted, “it was also about improving the lives of ordinary people.”

Natasha visits the Ding County Memorial Site

She also visited the Ding County Memorial Site, located about half an hour outside the city, where dedicated memorial halls commemorate each of the key researchers. Natasha was moved by the way these stories have been preserved and extended into the present. “I was especially grateful to meet and thank not only the scholars continuing this legacy today, but also the descendants of those villagers who once opened their homes to my great-grandfather.”

Natasha confessed that she hadn’t formed a clear image of what Ding County would look like today. “I imagined something more rural,” she admitted. “But what I found was a modern city surrounded by beautiful countryside.” It was her first time visiting rural China, and the experience left a strong impression. “The landscape was peaceful, and it helped me better understand what my great-grandfather might have seen — and hoped for.”

Natasha (front row, 2nd from the right) at University of Zurich

When asked what her great-grandfather would feel today, Natasha thought that he would be pleased. She said, “China has made enormous progress over the past century. Seeing that Ding County is now a thriving area, and that his research is still being continued by scholars from institutions like Renmin University of China, I believe he’d feel that his work truly had meaning.”

As spring blossoms on the campus of Peking University, the past quietly flows into the present. The story of Franklin Lee and Natasha is no longer just about academic legacy —it is about continuity, memory, and renewal. It reminds us that history is not frozen in archives. Sometimes, it walks beside us — in speech, in tribute, and in the act of returning.

Written by: Hou Qianchen

Edited by: Zhang Jiang, Chen Shizhuo

Photo credit to: Natasha, Hou Qianchen, He Shu