[70 years on] Ji Xianlin: The aspiration and mission of a polyglot

Dec 25, 2019

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series of articles celebrating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Each article shines the spotlight on one PKUer who has made remarkable contributions to China’s recent development, highlighting not only the importance of their individual accomplishments, but also the significant impact Peking University has had on China’s development over the past 70 years.

Ji Xianlin, a Chinese historian and Indologist who received high honor and awards from the governments of China and India, remains an outstanding icon in the community of intelligentsia. However, his contribution to knowledge, unsurpassable and unparalleled, earned himself more than ever-lasting academic reputation. People remember him not only as a professor and scholar, but also as a philosopher of great importance who motivated the young generation to reflect on the development of knowledge and encouraged them to devote themselves to the growth of society.

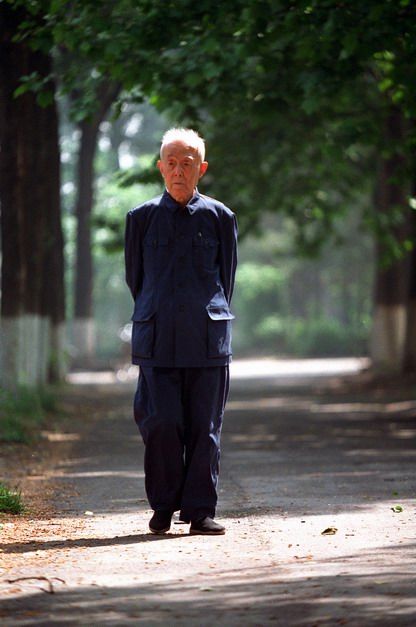

Ji Xianlin

Ji Xianlin

East or west, home is the best

Born in 1911 in Linqing, Shandong, an impoverished province, Ji Xianlin or 季羡林 (his Chinese name), was the only son in his family. So destitute that Ji’s parents couldn’t even support their only child with noodles and salt, but determined that they should let him receive proper education. At the age of six, Ji Xianlin was sent to one of his uncles who settled down in Jinan, the capital and the largest city in Shandong province, in order to go to school. Ji saw his mother again only once for a funeral, and then another time at her own funeral when he was a college student at the Department of Western literatures (Today’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures) at Tsinghua University.

In 1935, one year after his graduation from Tsinghua University, Ji boarded a train from Peiping to Manchuria, which was at that time occupied by the Japanese. He then travelled the Trans-Siberian Railway across the Soviet Union, a government he resented on account of the issue of the independence of Outer Mongolia. He eventually disembarked in Berlin, and arrived at the University of Göttingen where he started to study languages of ancient India: Sanskrit, Pali, and Tokharian.

Ji Xianlin (left) with his classmate in Germany

Ji Xianlin (left) with his classmate in Germany

In Göttingen, not only did he study three rare ancient Indian languages, but also Arabic, Russian, Serbian, Croatian, and literature. Ji’s sojourn in Germany was during the catastrophic WWII, but thanks to his observant eyes, he left with a profound understanding of the irrevocable impact a long-lasting and unnecessary war could have. He would carry with him the memory of an irrational and violent society under Hitler’s Nazi rule. Ji was desperately longing to return to China, on the one hand, hoping to escape the disastrous war and Germany’s dim future on the brink of surrender. On the other hand, Ji was itching to bring back what he had learnt in Göttingen to advance China’s development.

After obtaining his Ph.D., through the assistance of Chen Yinque, a remarkably prominent historian, Ji was introduced to Peking University, and flew back from Germany to become director of the Department of Eastern Languages and Literatures.

Although Ji's own study mainly focused on the languages of ancient India, world literature, the gradual development of Buddhism, and Sino-Indian relations, he was sincerely selfless and diligently devoted to furthering the performance of other specialties. In 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was founded, Ji received a personal letter written by Qiao Guanhua, who was Chinese foreign minister from 1974 to 1976. In the letter, Qiao touched upon the possible coalescence of different departments of universities in Nanjing under the coordination of PKU Department of Eastern Languages and Literatures. Qiao also said that, with the sociopolitical atmosphere changed and diplomatic situation altered, the nation was in desperate need of scholars whose expertise would aid the PRC on issues related to East Asia, better if they have an outstanding command of languages.

From then on Ji didn't take a day off, and assiduously started to arrange for new teachers dormitories and food, transportation and education plans, even welcoming in person these newcomers at the station.

Ji Xianlin at Peking University

Burgeoning development under Ji’s leadership

As the director of the Department of Eastern Languages and Literatures at Peking University, Ji immersed himself in this laborious job. At a time when food was in scarcity, cash in shortage, and professors were paid in foxtail millet, Ji was so successful that the department’s number of people soared dramatically from no more than ten in 1946, to the biggest department at Peking University in 1952. In addition to increasing the size of the department, the quality improved enormously as well, on account of the fact that Ji and Hu Shih, who took up the post of president of Peking University in 1946, together invited numerous intellectuals who had studied abroad. At that time, if people studied abroad, especially in the U.K, France, Germany, the Soviet Union, and the United States, they were usually exceptionally brilliant, since it took great perseverance to overcome challenges brought by poverty and war to attain scant national scholarship.

Ji hoped that these professors would impart as much of their knowledge as possible to students, and Ji had an additional obligatory task for them: English. Although the department engaged in the research of East Asian languages and literature, even providing chances to study rare languages, such as Sanskrit, Pali, Mongolian, and Tibetan, Ji was a fervent advocate for English. He once said, “I demand students who study Eastern languages to study English as well, a principle in which I persist. There is no chance that one can never study English. Being solely dependent on Eastern languages does not work.”

Due to Ji’s persistence since he was elected as vice president of Peking University in 1978, the department flourished with great academic performance, producing scholars and experts in great multitude and publishing a considerable number of history-related books and dictionaries. Ji described the year 1978 as a momentous watershed. Following the implementation of the policy of Reform and Opening-up in 1978, scholars can think more freely and independently, leading to the active exchanges of different thoughts in the academia, Ji added.

In 1978, not only did Ji become vice president of Peking University, he also assumed the duty of the director of the Graduate School of South Asian Studies whilst still leading the Department of Eastern Languages and Literatures. Although Ji was heavily burdened with conferences, he continually dedicated himself to the affairs at Peking University. Ji was so wholehearted that once when he was lying on his bed the telephone rang, “Vice President Ji, water is running out at our building…please respond as soon as possible!”

Ji was considerably admired by his students, and was such a modest character. Once upon a time, a student mistook him as a custodian and gave him luggage to carry, to which Ji attended to. It was scorching that day. The student came back and found Ji, who he still didn’t recognize as vice president, reading and waiting for him at ease. The day after, when the student realized at the opening ceremony, the vice president who was speaking on stage was exactly the man who had helped him with his luggage yesterday, he was more than surprised.

Ji Xianlin outside Peking University Library

Ji Xianlin outside Peking University Library

A strong advocate for patriotism

What motivated Ji's love for his students was his desire to see the next generation of China, in his own words, “bear the responsibility of the world”, and to be patriotic since, “patriotism is what we need the most”. Ji dedicated his whole life, patriotically and selflessly, to ancient Indian languages and to the Sino-Indian relations, which led to his undisputed fame as a linguist and Indologist.

After Ji passed away on July 11, 2009 in Beijing, former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, paid an official visit to his cremation to show a state-level homage. Former Indian Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, also expressed his condolence to Wen, stating that “Ji was one of the most famous Indologists in the world. Ji is a knowledgeable scholar on Buddhism and the 1,000-year-old history of India-China cultural exchanges. Ji played a key role in boosting China’s understanding of the Indian culture. Ji’s death made India lose a true friend and an outstanding person advocating the continuing development of the bilateral ties that have lasted for thousands of years.

Written by: Chen Ching-Shan

Edited by: Ciara Morris, Huang Weijian