Peking University, February 9, 2026: Modern technologies increasingly rely on light sources that can be reconfigured on demand. Think of microlasers that can quickly switch between different operating states—much like a car shifting gears—so that an optical chip can route signals, perform computations, or adapt to changing conditions in real time.

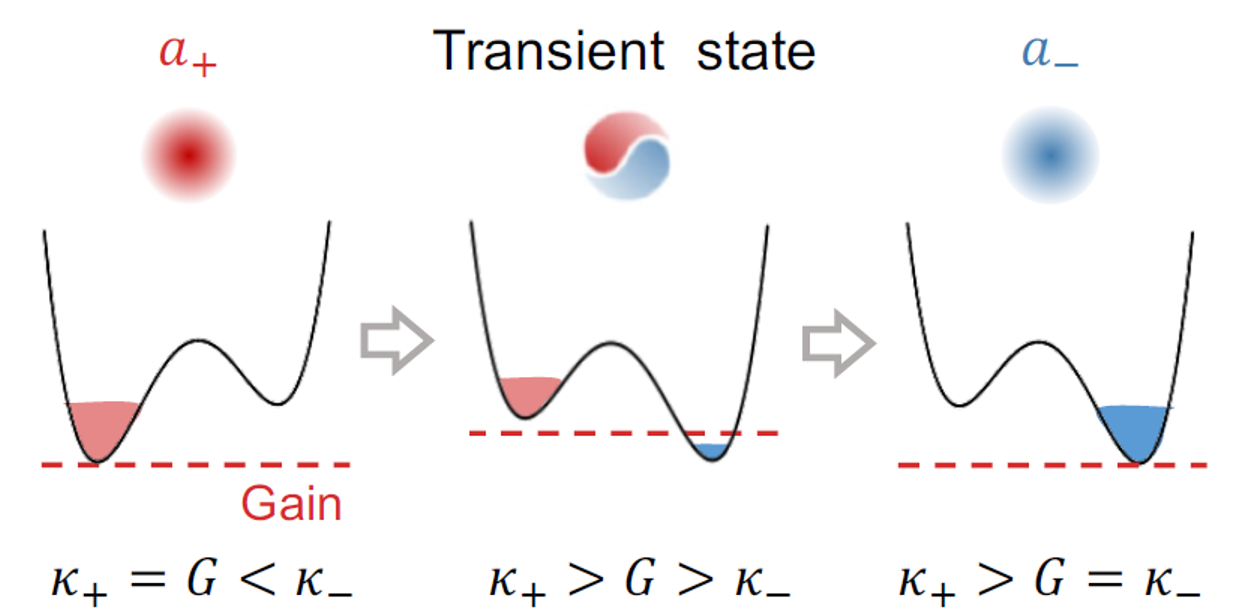

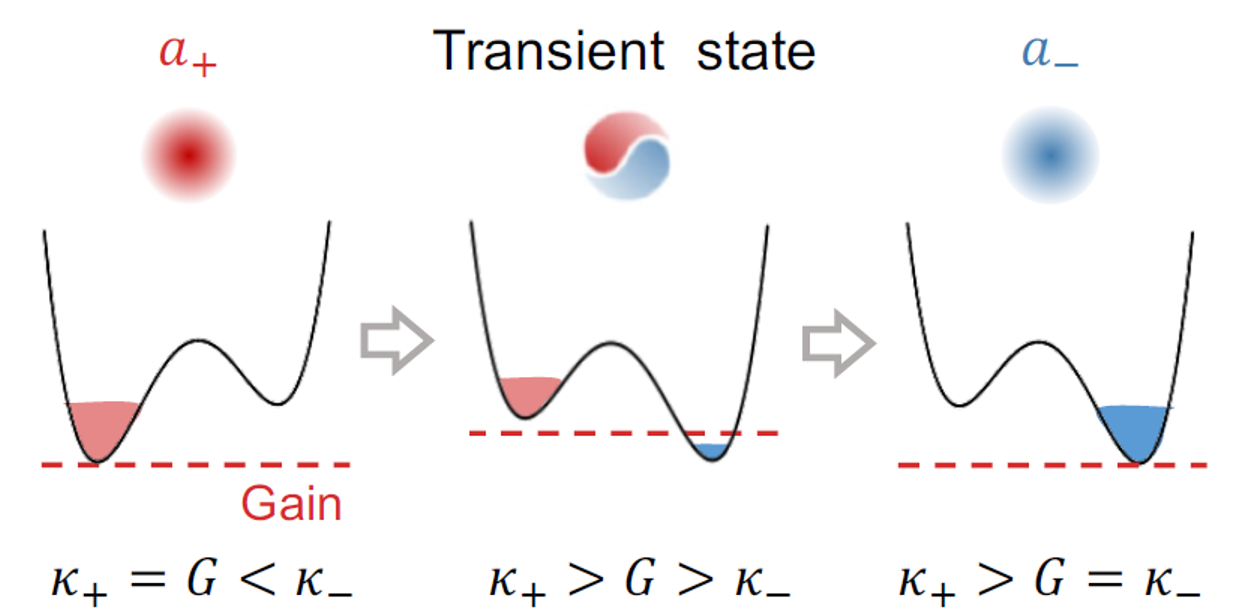

The microlaser switching is not a smooth, leisurely process, but can be sudden and fast. Generally, nearly identical "candidate" lasing states compete with each other in a microcavity, and the laser may abruptly jump from one state to another when external conditions are tuned (Figure 1). This raises a practical question: how fast can such a switch be, in principle? For physicists, it raises a deeper one: does the switching follow a universal rule, like other phase transitions in nature?

A team at Peking University has now provided a clear picture for an ultrahigh-quality microcavity laser: the time the laser needs to complete a state switch follows a remarkably simple power-law rule. When the control knob is swept faster, the switch becomes faster—but not arbitrarily so. Instead, the switching time decreases with the square-root of the sweep speed, corresponding to a robust exponent close to 1/2. This result effectively sets a speed limit for how quickly such microlasers can "change gears."

Figure 1. Schematic of the microlasers switching process between nearly degenerate supermodes with the photon population.

How to control the laser switch?

Figure 1. Schematic of the microlasers switching process between nearly degenerate supermodes with the photon population.

How to control the laser switch?

In an ultrahigh-Q cavity, photons circulate many millions of times before leaking out, which greatly enhances light–matter interactions and enables low-threshold lasing. Until now, most studies could tell which state the laser ended up in, but it was much harder to capture the switching process itself—the brief transient where the laser leaves one state and settles into another. That transient can unfold on nanosecond timescales, and it happens in an open system that is constantly driven and losing energy, where noise and dissipation play central roles.

To solve this, the team built a micro-laser platform that can be tuned in a clean and programmable way. The laser is generated in an ultrahigh-Q silica microsphere—only tens of micrometers across—where clockwise and counter-clockwise waves can couple and form two competing standing-wave states (two "supermodes") with opposite symmetries.

The key idea was to add a feedback loop that reinjects a small portion of the laser light back into the cavity. By controlling the phase of this reinjected light, the researchers could make interference either strengthen or weaken specific supermodes. In effect, this phase control lets them tune the loss balance between the two competing lasing states—like adjusting a seesaw—so that the system can be swept across the critical point where one state becomes favored over the other. This is a distinctly "non-Hermitian" form of control: rather than only shifting resonance frequencies, it directly reshapes the gain–loss landscape that governs which state wins.

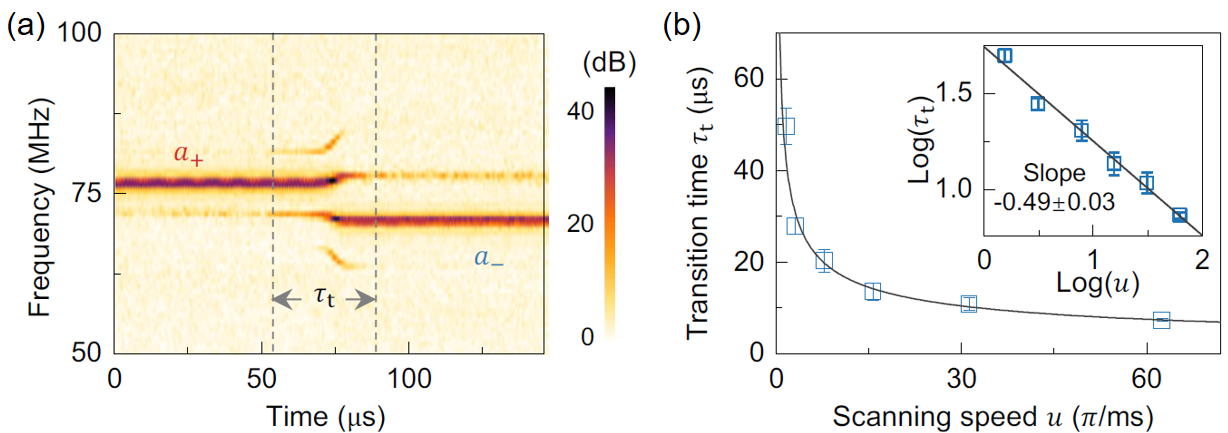

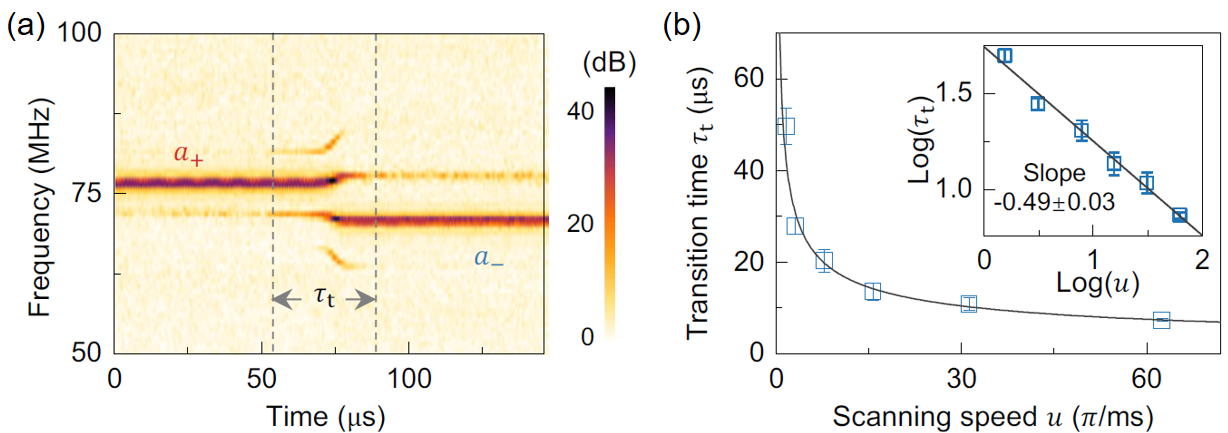

Figure 2. (a) Measured dynamic switching process between two lasing states. (b) Power scaling law of the transition time versus the scanning speed of the control parameter.

Filming the switch in real time

Figure 2. (a) Measured dynamic switching process between two lasing states. (b) Power scaling law of the transition time versus the scanning speed of the control parameter.

Filming the switch in real time

Controlling the switch is only half the story—recording it is the other half. The team used a radio-frequency (RF) beat-note method: they mixed the laser output with a stable reference and tracked the resulting RF signal over time. This converts ultrafast optical changes into measurable electrical signals, allowing the researchers to reconstruct how the laser state evolves during the switch with sub-10-nanosecond time resolution. This is like turning an invisible internal jump into a measurable "high-speed movie": the moment the system crosses the critical point, the old state fades and the new state rises, producing a clear transient signature that can be quantified (Figure 2).

The simple rule: a spower scaling

Once the transient is visible, a natural experiment becomes possible: repeat the switching protocol many times, but sweep the control knob at different speeds. The team then extracted a well-defined transition time from each switching event. The result was striking: across a broad range of sweep speeds, the transition time follows a robust power law. Faster sweeps lead to faster switching, but the improvement slows down in a predictable way.

Quantitatively, the switching time scales approximately as the inverse square root of the sweep speed, corresponding to an exponent close to 0.5. The same behavior also appears in studies of coupled-cavity laser networks, suggesting the rule is not a fragile feature of one device, but instead reflects a broader principle of non-equilibrium switching in driven, dissipative photonic systems.

"Universal scaling laws are valuable because they give engineers and scientists a predictive compass," said Prof. Xiao, the corresponding author of this research work. "Rather than tuning devices by trial and error, one can use a scaling rule to anticipate how changing control speed affects response time—and to understand where diminishing returns set in."

For applications, this finding may inspire the reconfigurable microlasers that must rapidly switch operating states for on-chip photonics and also the coupled laser networks proposed for optimization and analog computing, where many nodes must switch reliably and quickly. For fundamental science, the result provides a rare, clean experimental benchmark for non-equilibrium critical dynamics in an open, non-Hermitian setting—an arena where classic ideas about phase transitions must be rethought and tested.

The work, entitled “Power-law scaling of lasing-state switching in optical microcavities,” has been published in Physical Review Letters.

Read more: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/s2x6-5k55

Source: School of Physics, Peking University

Edited by: Chen Shizhuo